Mini Project 3: Text Mining and Analysis

Due: 10:50 am, Tue 10 MarIntroduction

In this assignment you will learn how to use computational techniques to analyze text. Specifically, you will access text from the web and social media (such as Twitter), run some sort of computational analysis on it, and create some sort of deliverable (either some interesting results from a text analysis, a visualization of some kind, or perhaps a computer program that manipulates language in some interesting way).

Skills Emphasized

- Accessing information on the Internet programmatically

- Parsing text and storing it in relevant data structures

- Choosing task-appropriate data structures (e.g. dictionaries versus lists)

- Computational methods for characterizing and comparing text

- Considering alignment between the topic that you want to analyze, the data sources at your disposal, and the state of software tools available to you for dissecting the data.

How to proceed

This is an individual assignment that each student will complete, starting by accepting the assignment in Github classroom by clicking this link. Once you’ve accepted the assignment, clone the repository on your computer.

You should read this document in a somewhat non-linear/spiral fashion:

- Scan through Part 1 to get a sense of what data sources are available. Try grabbing text from one of the sources that interests you. You do not need to try all the data sources.

- Scan through Part 2 to see a bunch of cool examples for what you can do with your text.

- Choose (at least) one data source from Part 1 or elsewhere and analyze/manipulate/transform that text using technique(s) from Part 2 or elsewhere.

- Write a brief document about what you did (Part 3)

Here are some resources with different examples of text mining:

- Computational Ethics Project Ideas for CMU Course

- Sentiment Analysis in Elections

- A Survey on Sentiment Analysis Challenges

- 10 Text Mining Examples

Suggested Milestones

Time management will be important for this project. It is divided into three parts, but they are all due on the same day. You are encouraged to start early, work steadily, and seek help often.

Since you have so much freedom on this project there’s not one proper path for everyone, but you should consider the following suggested timeline:

- By the first class session following the Mini-Project 3 kickoff…

- you should have attempted to secure text from at least one or two of the sources listed (or others you deem appropriate).

- By the second class session following the kickoff…

- you should have a means of locally storing data from the source you have selected.

- By the third class session following the kickoff…

- Your code should have the elements of an organized structure in place. We expect that your final submission will be a proper program in which you define multiple well-thought out functions (rather than a basic script starting point with just a flat list of commands). We also encourage you to try using classes if the understanding is there to do so.

- Some additional planning advice:

- The Project Write-up and Reflection is described after the implementation work. However, you may find it beneficial to write the “Project Overview” and a draft of the “Implementation” and “Results”, early in the process. The Implementation may be vague and you will likely need to revise it later, and the results can sketch what you hope to find instead of presenting hard data, but this kind of endpoint-first design can help guide your implementation work.

Part 1: Harvesting text from the Internet

The goal for Part 1 is for you to get some text from the Internet with the aim of doing something interesting with it down the line. As you approach the assignment, we recommend that you get a feel for the types of text that you can grab, below. However, before spending too much time going down a particular path on the text acquisition component, you should look ahead to Part 2 to understand some of the things you can do with text you are harvesting. The strength of your mini project will be in combining a source of text with an appropriate technique for language analysis (see Part 2).

Preliminaries

You are not required to use any particular Python package to complete this assignment. However, we recommend the Requests package to retrieve HTML pages from the web, and the NLTK package to analyze text, and the Vader sentiment analysis algorithm (included with NLTK).

To make sure that Requests is working properly, try these commands in Python:

>>> import requests

>>> print(requests.get('http://google.com').text)

If Requests is installed correctly, you should see the HTML from Google’s front page.

A Note About API Keys

For some of these data sources you will be generating some sort of secret authentication key. The tempting thing to do is to insert this secret right into your code, and then check it into GitHub. The problem with this is that in cases where your repository is public, someone might actually find your API key and use it themselves. While we are not requiring you to follow best practices in this assignment with your API keys (after all your repository is private), if you want to start practicing good habits, we have a notebook that walks you through ways to handle private keys with version controlled code.

Considerations for Selecting Data Sources

When you submit this assignment, you will be including a reflection in your write-up that discusses (roughly a paragraph each):

- The set of questions you had that sparked your exploration, and what you imagined an answer might look like upon completion.

- Why you felt that the data source(s) you selected could help you explore those questions. What were the limitations?

- How well the tools that you employed to analyze the data served you during the exploration. How confident are you in the answers yielded? What were the tools’ limitations?

Data Source: Project Gutenberg

Project Gutenberg is a website that has 42,000 freely available e-books. In contrast to some sites (sorry no link), this site is 100% legal since all of these texts are no longer under copyright protection. For example, the website boasts 171 works by Charles Dickens. Perhaps the best thing about the texts on this site is that they are available in plain text format, rather than PDF which would require some additional computational processing to process in Python.

In order to download a book from Project Gutenberg you should first use their

search engine to find a link to a book that you are interested in analyzing.

For instance, if you decide that you want to analyze Oliver Twist you would click

on this link from the Gutenberg search

engine. Next, you would copy the link from the portion of the page that says

“Plain Text UTF-8”. It turns out that the link to the text of Oliver Twist

is http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/730.txt.utf-8. To download the text

inside Python, you would use the following code:

import requests

oliver_twist_full_text = requests.get('http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/730.txt.utf-8').text

print(oliver_twist_full_text)

Note, that there is a preamble (boiler plate on Project Gutenberg, table of contents, etc.) that has been added to the text that you might want to strip out (potentially using Python code) when you do your analysis (there is similar material at the end of the file). The one complication with using Project Gutenberg is that they impose a limit on how many texts you can download in a 24-hour period (which lead to me getting banned the other day). So, if you are analyzing say 10 texts, you might want to download them once and load them off disk rather than fetching them off of Project Gutenberg’s servers every time you run your program (see the Pickling Data section for some relevant information on doing this). However, there are many mirrors of the Project Gutenberg site if you want to get around the download restriction.

Data Source: Wikipedia

We recommend the wikipedia package:

$ pip install wikipedia

The official documentation is here.

Some examples from the Quickstart section of the documentation follow:

>>> import wikipedia

>>> wikipedia.summary("Olin College")

"Olin College of Engineering (also known as Olin College or simply Olin) is a private undergraduate engineering college in Needham, Massachusetts, adjacent to Babson College. Olin College is noted in the engineering community for its youth, small size, project-based curriculum, and large endowment funded primarily by the F. W. Olin Foundation. The college covers half of each admitted student's tuition through the Olin Scholarship."

>>> olin = wikipedia.page("Olin College")

>>> olin.title

'Franklin W. Olin College of Engineering'

>>> olin.content

'Olin College of Engineering (also known as Olin College or simply Olin) is a private....'

>>> olin.images

['https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a8/OlinCollege.jpg',

'https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/9/9d/Olin_College_at_Night.jpg',

'https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/c/c0/Olin_Center_Sunset.JPG',

'https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/9/9b/Olin_College_Great_Lawn.jpg',

'https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/4/4d/OlinCollege.png']

>>> olin.links[:5]

['A cappella',

'Academic honor code',

'Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology',

'American Society of Mechanical Engineers',

'Amherst College']

Data Source: Twitter

Create a Twitter application here.

Use can use your GitHub profile as the website if you wish. It doesn’t actually matter all that much what you put here. For example,

https://github.com/yourusernamehere. Leave the Callback URL blank.

Copy the Consumer Key (API Key) and Consumer Secret (API Secret). You will need these below. Click on “manage keys and access tokens” to see the Consumer Secret. On that page, click “Generate Access Token”, and copy the Access Token and Access Token Secret too.

We recommend the python-twitter package. The documentation is here.

$ pip install python-twitter

Use the following code to see tweets in a particular user’s timeline, where

CONSUMER_KEY etc. are the Consumer Key and other credentials that you saved above.

import twitter

api = twitter.Api(consumer_key=CONSUMER_KEY,

consumer_secret=CONSUMER_SECRET,

access_token_key=ACCESS_TOKEN_KEY,

access_token_secret=ACCESS_TOKEN_SECRET)

api.GetUserTimeline(screen_name='gvanrossum')

This prints something like this:

[Status(ID=830854729710186496, ScreenName=gvanrossum, Created=Sun Feb 12 19:02:58 +0000 2017, Text='@ntoll Without context this stream of 10 tweets made little sense to me. :-('),

Status(ID=830577788901945345, ScreenName=gvanrossum, Created=Sun Feb 12 00:42:30 +0000 2017, Text="@swhobbit @github @brettsky IIUC every developer has a full clone in their .git -- it doesn't get much better than that."),

Status(ID=830194194501099520, ScreenName=gvanrossum, Created=Fri Feb 10 23:18:14 +0000 2017, Text='The CPython source code has officially moved to https://t.co/0ax0UGzgLZ. Congrats @brettsky !!!'),

Status(ID=830187573049896960, ScreenName=gvanrossum, Created=Fri Feb 10 22:51:56 +0000 2017, Text='Micro mypy update: https://t.co/XU6N0O88g5 -- the only change is fixing the typed_ast version, to avoid a new typed_ast breaking old mypy.'),

Status(ID=829017268096937985, ScreenName=gvanrossum, Created=Tue Feb 07 17:21:33 +0000 2017, Text='@FieryPhoenix7 Yes, I interviewed the Dropbox engineers thoroughly. :-)')]

See the package wiki for more examples.

Data Source: Reddit

At the terminal command line, install the Python

PRAW package:

$ pip install praw

Follow the instructions here to create a Reddit application. The random string of letters and numbers at to the right of the icon is the Client Id. The secret beneath the icon is the Client Secret. Save these.

Here’s an example adapted from the PRAW docs page.

CLIENT_ID and CLIENT_SECRET are the ones you saved above.

import praw

r = praw.Reddit(user_agent='text_mining', client_id=CLIENT_ID, client_secret=CLIENT_SECRET)

submissions = r.subreddit('opensource').hot(limit=5)

print([str(x) for x in submissions])

Disclaimer: The instructors have run the example above, but haven’t explored this package any more deeply. It’s possible that you will run into a roadblock with it.

Data Source: HTML Pages

Much data on the web is in the form of HTML, which is a mixture of human-language text,

and HTML markup such as <div> and <p>. You can use the Beautiful Soup package to extract

the text from an HTML page.

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import requests

html = BeautifulSoup(requests.get('https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franklin_W._Olin_College_of_Engineering').text, 'lxml')

html.find('p') # find the first paragraph

str(html.find('p')) # the first paragraph, as a string. Includes embedded <b> etc.

Use Python regular expressions to remove the embedded <b> etc.

import re

re.sub(r'<.+?>', '', str(html.find('p')))

[This is not a robust way to do this. A robust way involves using a recursive function.]

Additional Possible Data Sources

In addition to the sources described above, which have been tested, we have some additional suggestions that are more in the exploratory stage. If you have success using these sources, please share it with us!

Google Search

$ pip install google

Then to perform a search, you can use the following.

import googlesearch

for result in googlesearch.search(query='Computer Science'):

print(result)

This is a method of accessing Google search results based on the idea of webscraping. In this approach, you are basically downloading the human readable HTML page from Google, and then attempting to extract a structured description of the page. If you want to use Google’s API (which will give you structured results directly), you can use Google’s official Python package. Unfortunately, using the official package is much more involved than using the library above.

Additional Corpora

There’s a fantastic list of text corpora available on this Wikipedia page. Some of the corpora are American English, some are British English, and some are specialized to a particular topic (e.g., US laws).

Pickling Data

For several of these data sources you might find that the API calls take a

pretty long time to return, or that you run into various API limits. To deal

with this, you will want to save the data that you collect from these services

so that the data can be loaded back at a later point in time. Suppose you have

a bunch of Project Gutenberg texts in a list called charles_dickens_texts.

You can save this list to disk and then reload it using the following code:

import pickle

# Save data to a file (will be part of your data fetching script)

f = open('dickens_texts.pickle', 'wb')

pickle.dump(charles_dickens_texts, f)

f.close()

# Load data from a file (will be part of your data processing script)

input_file = open('dickens_texts.pickle', 'rb')

reloaded_copy_of_texts = pickle.load(input_file)

The result of running this code is that all of the texts in the list variable

charles_dickens_texts will now be in the list variable

reloaded_copy_of_texts. In the code that you write for this project you

won’t want to pickle and then unpickle in the same Python script. Instead, you

might want to have a script that pulls data from the web using the APIs

above and then pickles them to disk. You can then create another program for

processing the data that will read the pickle file to get the data loaded into

Python so you can perform some analysis on it.

For more details and practice, check out the Pickling Project Toolbox assignment.

Part 2: Analyzing Your Text

Considerations for Your Analysis

When you choose an approach to analyze your test, think about how this approach can and can’t answer the questions you want to ask of the text data you have. To what degree do you consider the data capable of providing an answer that is convincing (to you, or others). Did you make any assumptions about how the data was collected? In the write-up, include how you might mitigate limitations of your analysis if given more time.

Characterizing by Word Frequencies

One way to begin to process your text is to take each unit of text (for instance a book from Project Gutenberg, or perhaps some Tweets regarding a topic of interest) and summarize it by counting the number of times a particular word appears in the text. A natural way to approach this in Python would be to use a dictionary where the keys are words that appear and the values are frequencies of words in the text (if you want to do something fancier look into using TF-IDF features).

Computing Summary Statistics

Beyond simply calculating word frequencies there are some other ways to summarize the words in a text. For instance, what are the top 10 words in each text? What are the words that appear the most in each text that don’t appear in other texts? For some other ideas see Chapter 13 of Think Python.

Doing Linguistic Post-processing

Vader (note: before doing this you’ll need to download the NLTK corpora by running the command $ python -m nltk.downloader all)

from nltk.sentiment.vader import SentimentIntensityAnalyzer

analyzer = SentimentIntensityAnalyzer()

analyzer.polarity_scores('Software Design is my favorite class!')

This program will print out:

{'compound': 0.5093, 'neg': 0.0, 'neu': 0.603, 'pos': 0.397}

NLTK provides a number of other really cool features. Some examples of this include: part of speech tagging, and full sentence parsing. You can also do sentiment analysis within NLTK by training a Bayesian classifier (code).

If you perform some linguistic post processing, you may be able to say something interesting about the text you harvested from the web. For example, if you listen to a particular Twitter hashtag on a political topic, can you gauge the mood of the country by looking at the sentiment of each tweet that comes by in the stream? There are tons of cool options here!

Text Similarity

It is potentially quite useful to be able to compute the similarity of two texts. Suppose that we have characterized some texts from Project Gutenberg using word frequency analysis. One way to compute the similarity of two texts is to test to what extent when one text has a high count for a particular word the other text also a high count for a particular word. Specifically, we can compute the cosine similarity between the two texts. This strategy involves thinking of the word counts for each text as being high-dimensional vectors where the number of dimensions is equal to the total number of unique words in your text dataset and the entry in a particular element of the vector is the count of how frequently the corresponding word appears in a specific document (if this is a bit vague and you want to try this approach, ask an instructor).

We tried this on some Project Gutenberg texts from two authors: Charles Dickens and Charles Darwin. The table below shows the pair-wise similarities between the Charles Dickens texts (note that 1 is perfect similarity):

[[1. 0.90850572 0.96451312 0.97905034]

[0.90850572 1. 0.95769915 0.95030073]

[0.96451312 0.95769915 1. 0.98230284]

[0.97905034 0.95030073 0.98230284 1.]]

The pairwise similarities between Dickens and Darwin (we just used one Darwin text) are:

[[0.78340575]

[0.87322494]

[0.83381607]

[0.82953109]]

Notice that all of the similarities between Dickens and Darwin are lower than for Dickens novels to other Dickens novels. This suggests that this technique can be used for author identification (for instance in the case of a work of unknown authorship). You could also use it to try and guess which of your friends has authored a particular post!

These similarity values can be assembled into a similarity matrix that compares each work with all other works.

[[1., 0.90850572, 0.96451312, 0.97905034, 0.78340575],

[0.90850572, 1., 0.95769915, 0.95030073, 0.87322494],

[0.96451312, 0.95769915, 1., 0.98230284, 0.83381607],

[0.97905034, 0.95030073, 0.98230284, 1., 0.82953109],

[0.78340575, 0.87322494, 0.83381607, 0.82953109, 1.]])

Text Clustering

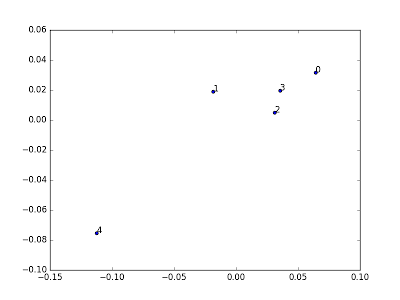

If you can generate pairwise similarities (say using the technique above), you can Metric Multi-dimensional Scaling (MDS) to visualize the texts in a two dimensional space. This can help identify clusters of similar texts. Here is a particularly inspiring example by Matthew Jockers (check out the University of Nebraska’s press release on the paper).

In order to apply MDS to your data, you can use the machine learning toolkit

scikit-learn. scikit-learn should have been installed by default when you installed Anaconda. However, if you get an error trying to import the sklearn module, let us know. See our Toolbox on Machine Learning.

Here is some code that uses the similarity matrix defined in the previous section to create a 2-dimensional embedding of the four Charles Dickens and 1 Charles Darwin texts.

import numpy as np

from sklearn.manifold import MDS

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# these are the similarities computed from the previous section

S = np.asarray([[1., 0.90850572, 0.96451312, 0.97905034, 0.78340575],

[0.90850572, 1., 0.95769915, 0.95030073, 0.87322494],

[0.96451312, 0.95769915, 1., 0.98230284, 0.83381607],

[0.97905034, 0.95030073, 0.98230284, 1., 0.82953109],

[0.78340575, 0.87322494, 0.83381607, 0.82953109, 1.]])

# dissimilarity is 1 minus similarity

dissimilarities = 1 - S

# compute the embedding

coord = MDS(dissimilarity='precomputed').fit_transform(dissimilarities)

plt.scatter(coord[:,0], coord[:,1])

# Label the points

for i in range(coord.shape[0]):

plt.annotate(str(i), (coord[i,:]))

plt.show()

This will generate the following plot. The coordinates don’t have any special meaning, but the embedding tries to maintain the similarity relationships that we computed via comparing word frequencies. Keep in mind that the point labeled 4 is the work by Charles Darwin.

Markov Text Synthesis

You can use Markov analysis to learn a generative model of the text that you collect from the web and use it to generate new texts. You can even use it to create mashups of multiple texts. One possibility in this space would be to create literary mashups automatically. Think Python chapter 13 section 8 called “Markov Analysis” has some detail on how to do this. Again, let the teaching team know if you go this route and we can provide more guidance.

Text Classification

Using machine learning libraries like scikit-learn (which we talked about earlier in this writeup) you can create models that are able to automatically textual objects (e.g., words, paragraphs, sentences) into particular categories. These categories could be anything: positive versus negative product reviews, abusive versus non abusive language, etc.

We have put together a notebook that uses this approach to determine whether a sentence, taken completely out of context, comes from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein or Bram Stoker’s Dracula. By examining the way that the machine learning algorithm solves the task, we can learn a little bit about the underlying narrative structure of each work.

Part 3: Project Write-up and Reflection

Please prepare a short (suggested lengths given below) document with the following sections:

Project Overview [Maximum 200 words]

What data source(s) did you use and what technique(s) did you use analyze/process them? What did you hope to learn/create?

Implementation [~2-3 paragraphs]

Describe your implementation at a system architecture level. You should NOT walk through your code line by line, or explain every function (we can get that from your docstrings). Instead, talk about the major components, algorithms, data structures and how they fit together. You should also discuss at least one design decision where you had to choose between multiple alternatives, and explain why you made the choice you did.

Results [~2-3 paragraphs + figures/examples]

Present what you accomplished:

- If you did some text analysis, what interesting things did you find? Graphs or other visualizations may be very useful here for showing your results.

- If you created a program that does something interesting (e.g. a Markov text synthesizer), be sure to provide a few interesting examples of the program’s output.

Alignment [~3 paragraphs]

How much alignment did you find between what you set out to explore and the data and tools used to carry out the project? What was set of questions you had that sparked your exploration, and what you imagined an answer might look like upon completion? To what degree did you feel that the data source(s) you selected could help you explore those questions given its limitations? How well did the tools that you employed, given their limitations, serve you during the analysis. How confident are you in the answers they provided.

Reflection [~1 paragraph]

From a process point of view, what went well? What could you improve? How would you attempt to mitigate the data-related or tool-choice problems with your project? Other possible reflection topics: Was your project appropriately scoped? Did you have a good plan for unit testing? How will you use what you learned going forward? What do you wish you knew before you started that would have helped you succeed?

For grading purposes, the combination of the reflection/alignment/write-up and the slide you submit will account for 20% of the total grade.

Turning in your assignment

- Your code should be submitted as either (a) Python file (or files) that can be executed by running e.g.

python text_mining.py, or (b) a Jupyter notebook. - If you submit a Python file:

- The project README must describe how to install any required packages and how to run it (e.g.

python text_mining.py)

- The project README must describe how to install any required packages and how to run it (e.g.

- If you submit a Jupyter notebook:

- You must test that it behaves correctly when you execute “Run All” from the “Cell” menu.

- You must also submit a Python text file.

Use the File > Download as > Python menu item to download a text file, and

git addit to your repo.

- Submit your Project Write-up/Reflection. This can be in the form of:

- a Markdown file, committed to your repository, or

- a Jupyter notebook, committed to your repository, or

- a PDF document, committed to your repository, or

- a project webpage.

- Push your code to GitHub. You should also include a

README.mdfile in your repository briefly explaining your project and linking to your Project Write-up/Reflection. - Add a slide summarizing your work to the class presentation. See more details below.

- Submit on Canvas

Project Presentations

In order to share what you discovered/created as part of your text mining project and practice quickly presenting your programming work to an audience, you will include summary highlights in a class-wide Google slides presentation. This will pull largely from the Results section of your writeup, and should be to-the-point (about one slide) and visually interesting.

Professionalism is important in public presentations, so please use the “would I be happy for my parents to read this in the newspaper” test when uploading content. Humor is great; abusive language or disparaging groups of people is firmly not acceptable.