Day 9

Today

- A look ahead to next class

- Markov Analysis and more

- Memoization exercises

- Studio time

For next time

- MP2 is due Tuesday. If you’d like to participate in the gallery show (and we hope you do), please submit your art files and artist’s statement using the “Optional Artists Statement” assignment in Canvas before Monday 8PM.

- For Tuesday’s class we’ll meet in AC326 for the MP2 gallery show and MP3 kick-off.

- The next reading is longer than usual as we dive into Classes. Be sure to budget time for active reading and use Course Assistant hours.

Markov Analysis and more

Memoization

Last class, a lot of you had the chance to do this exercise:

Write a function called choose that takes two integer, n and k, and returns

the number of ways to choose k items from a set of n (this is also known as

the number of combinations of k

items from a pool of n). Your solution should be implemented recursively using

Pascal’s rule.

Here is a sample solution:

def nchoosek(n, k):

""" returns the number of combinations of size k

that can be made from n items.

>>> nchoosek(5,3)

10

>>> nchoosek(1,1)

1

>>> nchoosek(4,2)

6

"""

if k == 0:

return 1

if n == k:

return 1

return nchoosek(n - 1, k - 1) + nchoosek(n - 1, k)

if __name__ == '__main__':

import doctest

doctest.testmod(verbose=True)

It passes all the unit tests!!! Hooray!

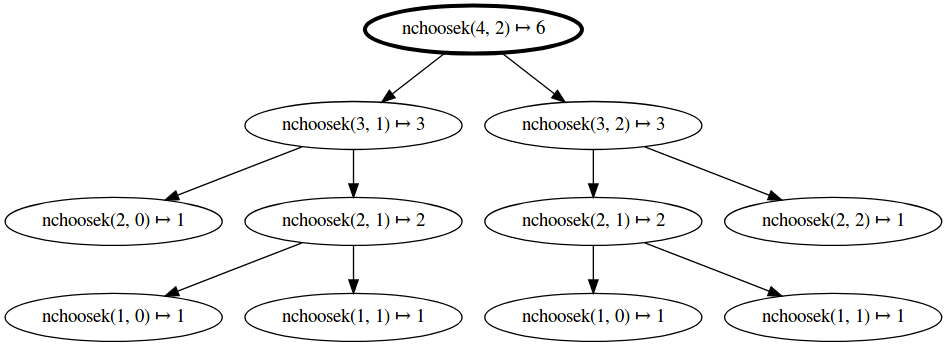

Unfortunately, this code is going to be quite slow. To get a sense of it, let’s draw a tree that shows the recursive pattern of the function.

You can even visualize the call graph within Jupyter notebook using an extension. In Linux:

$ sudo apt install graphviz

$ pip install callgraph

Then within your notebook, you can draw a call graph as a function is called:

%load_ext callgraph

%callgraph nchoosek(4, 2)

As you can see, the function is recursively called multiple times with the same arguments.

In order to improve the speed of this code, we can make use of a pattern called memoization. The basic idea is to transform a recursive implementation of a function to make use of a cache (in this case a Python dictionary) that remembers all previously computed values for the function. Here’s is a skeleton of a memoized recursive function (we are being a little fast and loose with the mixing pseudo code and Python, but this should become clearer as you do a concrete example.

def recursive_function(input1, input2):

if input1, input2 is a base case:

return base case result

if input1, input2 is in the list of already computed answers

return precomputed answer

return recursive step on a smaller version of input1, input2

Exercise: Add memoization to your implementation of nchoosek (and/or levenshtein_distance) and study its impact on performance.

Think Python Chapter 11.6-7 will also be helpful.

Going Beyond: Higher-Order Functions

Higher-order functions are functions that take a function as an argument and return a function as a value. This may be slightly mind-bending at first, but functions in Python are objects like everything else, so we can pass them around just as we pass ints and lists.

We’ve put together an optional Jupyter notebook that explores using higher-order functions to implement memoization. It also covers decorators, which is a Python syntax that makes it easier to apply higher-order functions.